I first met curator, writer and academic Sarah Cook when I was Director of Exhibitions at FACT in Liverpool, in 2004. Sarah was, at that time, engaged in pioneering work, establishing CRUMB (Curatorial Resource for Upstart Media Bliss), with co-founder Beryl Graham in Newcastle and Gateshead. Together they hosted workshops and courses worldwide and CRUMB was, and remains, a vital resource and network for curators of new media art.

Sarah continues to champion international artists working with technology, always creating new commissioning, funding and exhibiting opportunities for them. She thrives on immersing herself in deep research, has an enviable ability to retain facts and seamlessly weave the contemporary and historical to address the issues of our time. Throughout her work she marries the social, political and cultural spheres in order to help us re-imagine our engagement with technology, each other and how we shape the world around us.

Routine is important to give your mind time to wander. This might not get you to make art, but it might send you off down another research path which might later become part of your work.''

Please note this interview was first published on the Artist Mentor website during 2020.

In 2018, whilst I was Director of Programmes at Somerset House, the Director Jonathan Reekie and I invited Sarah to curate the exhibition 24/7 with Jonathan. As always, Sarah worked above and beyond, spinning academic, curatorial, writer and editor plates between Dundee, Glasgow and London, to ensure the show and catalogue were delivered in record time, and a success. This determination and tenacious dedication to her work is reflected in her habit of taking daily swims in the cold Northern sea.

Sarah Cook is Professor of Museum Studies in Information Studies at the University of Glasgow and based in Scotland. She has curated and co-curated international exhibitions of contemporary art and new media art including: 24/7: A Wake-up Call For Our Non-stop World (2019), Somerset House, 2019-20; The Gig Is Up, V2_Institute for Unstable Media, Rotterdam, 2016; Right Here, Right Now, The Lowry, Salford, 2015; Alt-w, the Royal Scottish Academy, SSA Annual Exhibition, Edinburgh, 2014; Not even the sky: Thomson & Craighead, MEWO Kunsthalle, Memmingen, 2013; Biomediations, Transitio_MX_05, Mexico City, 2013; Mirror Neurons, National Glass Centre, Sunderland, 2012; Q.E.D., AND Festival, Liverpool 2011; Untethered, Eyebeam, New York, 2008; Broadcast Yourself, AV Festival 08, Newcastle, 2008; Database Imaginary, 2004 and The Art Formerly Known As New Media, Walter Phillips Gallery, The Banff Centre, 2005.

Sarah is one of the curators behind Scotland’s only digital arts festival NEoN Digital Arts and was founding curator of LifeSpace Science Art Research Gallery in the School of Life Sciences, University of Dundee (2013-2018), where she curated 16 exhibitions including newly commissioned work from artists Mat Fleming, Heather Dewey Hagborg and Philip Andrew Lewis, Andy Lomas, Daksha Patel, the Center for Postnatural History, Helen and Kate Storey, Mary Tsang, Spela Petric and many others.

She is the editor of INFORMATION (Documents of Contemporary Art, Whitechapel and MIT Press, 2016) and co-author (with Beryl Graham) of Rethinking Curating: Art After New Media (MIT Press, 2010; Chinese edition 2016). Sarah has held a longstanding association with The Banff Center, developing exhibitions, summits, curatorial residencies and publications including co-editing with Sara Diamond Euphoria & Dystopia: The Banff New Media Institute Dialogues (Banff Centre Press, 2011). In 2008 Sarah was the inaugural curatorial fellow at Eyebeam Art and Technology Center in New York. She was curator of new media at BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art from 2004 until 2006, hosting residencies and projects from Germaine Koh, Lev Manovich, Darko Fritz and Studer / van den Berg. For 3 years she was an associate producer with Locus+. After completing her PhD at the University of Sunderland, she also curated exhibitions for the Reg Vardy Gallery and helped establish the MA Curating programme and Professional Development short course with CRUMB.

Sarah holds a Masters degree from the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College, New York (class of 1998) and is proud to have begun her professional career as a curatorial researcher in the longstanding internship program at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis working on exhibitions with Yayoi Kusama and Lorna Simpson.

What are you doing, reading, watching or listening to now, that is helping you to stay positive?

During lockdown there were some new relaxing weekend routines (involving issues of Grazia and chocolate Magnums for instance) but there wasn’t one thing. Unless you count the Netflix production of Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events, which I’d been meaning to watch for years having loved the books, and it didn’t let me down. The world is quiet here. Whatever bad thing you think is just around the corner, it’s bound to be something worse. Look away.

Which is to say, I adopted a slight ‘ignorance is bliss’ or serendipitous happenstance approach to stop feeling overwhelmed, not just by the bad news, but by the amount of digital creative art content available to consume online and the pressure to be producing material to add to the discussions around it.

Given my academic post in museum studies, I should be writing about the massive change museums have experienced during lockdown. As a sometime historian of new media and digital art I should be tweeting non-stop about this thing called online art that museums are only now discovering. I am doing a bit of both, but it is not possible to do only that given the projects I have on the go and all the time-pressured tasks that come with University work (not least planning for an uncertain year ahead). Despite lockdown lifting and museums and galleries now open again, it’s still not over. I’m watching it all, taking notes, lodging these cultural shifts in my memory, they’ll come in handy later.

I’ve been able to stay positive by not guilt-tripping myself if I miss being part of a conversation thread online, or by delighting in the serendipity of checking social media and finding a link to a live discussion or performance happening right that minute and tuning in for as long as I can. I’ve given myself permission to be both present and absent. Or as Lemony Snicket would say, to do something else right now if it will save my life: “There are times to stay put, and what you want will come to you, and there are times to go out into the world and find such a thing for yourself.”

Installation view of the exhibition The Gig is Up!, 2016 Curated by Sarah Cook for V2_,showing crowd-sourced drawings of clouds by self-employed creatives working on fiverr, by Addie Wagenknecht and Pablo Garcia

Installation view of the exhibition The Gig is Up!, 2016 Curated by Sarah Cook for V2_,showing crowd-sourced drawings of clouds by self-employed creatives working on fiverr, by Addie Wagenknecht and Pablo Garcia

Do you have an enthusiasm, specialism or a research focus that you bring to your teaching and academic practice?

I love works of art that take pieces of information and turn them into other, often networked, experiences. I like forging connections between early works made with networks or technology, with new works, often made for collective experience.

I have knowledge of media art history – including Internet art – and of the intersection of art and science (which has patches of history of technology and philosophy of science thrown in too). This might explain my curatorial choices.

So, for example, the large-scale exhibition 24/7: A Wake-Up Call For Our Non-Stop World at Somerset House (which I co-curated with Jonathan Reekie) included (among many other things!) Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg’s Machine Auguries, a light and sound installation based on an AI-generated dawn chorus, Thomson&Craighead’s BEACON, a flap sign displaying randomly a decade’s worth of Internet searches mixed with live searches, and Daily tous les jours I Heard There Was a Secret Chord – a room where you could collectively hum Leonard Cohen’s song Hallelujah, creating a choir based on the number of people listening to the track online around the world at that minute. All of these works used innovative software coding and to a certain extent ran live, some in a generative form.

And in the spin-off of 24/7, the show Sleep Mode (an online takeover I curated in June at Somerset House because the original show at Glasgow International in April was cancelled due to COVID-19) viewers could watch Addie Wagenknecht’s online security tips disguised as beauty tutorial videos, or Hyphen-Labs compilation of yawns taken in their facial recognition photo-booth, or hear Alan Warburton talk about the digital rendering of 3D ‘natural’ landscapes in virtual space, on-screen, and how at odds that feels with our desire to collectively experience real nature, off-screen.

lnstallation view of Daily tous les jours’ I heard there was a secret chord, seen in the exhibition 24/7: A Wake-Up Call For Our Non-Stop World, Somerset House, October 31 2019-February 23 2020. Photo courtesy of Somerset House

lnstallation view of Daily tous les jours’ I heard there was a secret chord, seen in the exhibition 24/7: A Wake-Up Call For Our Non-Stop World, Somerset House, October 31 2019-February 23 2020. Photo courtesy of Somerset House

I currently teach students who want to go on to work in the cultural heritage sector – galleries, libraries, archives and museums – and so to help them understand the practice of curating (and digital curation, which is not the same thing) I use these ‘lively’ interdisciplinary art works to foster discussion around big ideas that curators have to ask themselves, like, where is the audience? How much context is needed to understand this thing? What happens if the material a work uses is unstable – which part is worth preserving? Where or when does the art ‘happen’? Who is responsible for that encounter?

We are living through a huge shift in what we understand to be ‘cultural heritage’ if everything we produce digitally is now part of that. The cultural heritage sector has to rethink what role its institutions play in the creation of culture too. Digital art might tell us as much about the digital transformation of our lives as a defunct computer in a museum display case; bio-art might tell us as much about the major developments in life sciences as an unreadable genome sequence. The Instagram photos of the demonstrators toppling the statue of slaver Colston tell us more about this moment than the removed statue itself does. In a time of total information overload, where do we draw the line around what is a valuable piece of information and what isn’t? Is the Bristol Museum going to save the Instagram posts as well as the graffiti on the statue they dredged out of the harbour? Can we tell the difference between authentic and post-produced types of information (#fakenews)? Perhaps an artist can tell us. Or point us in the direction of the real story.

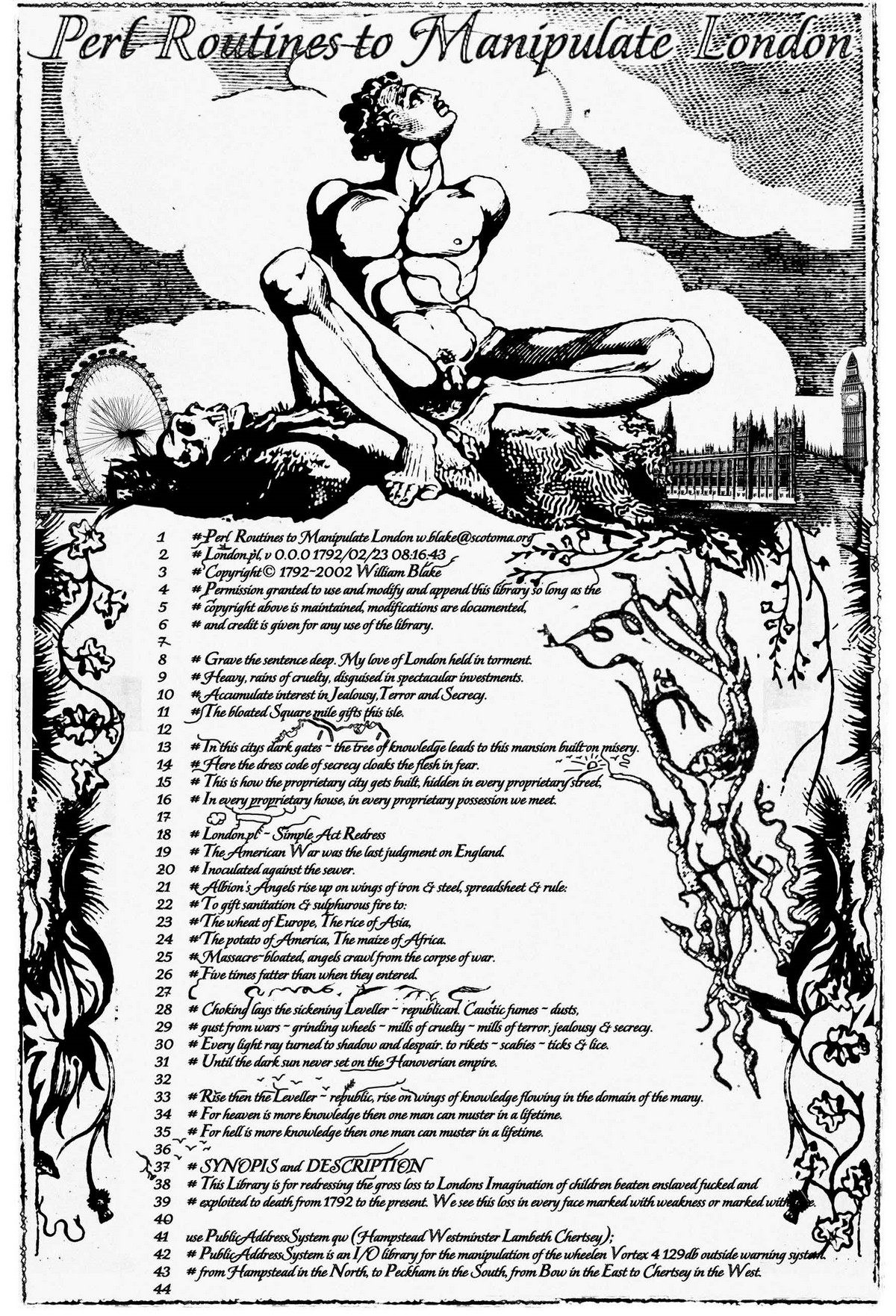

YoHa (Graham Harwood), Lungs-London.pl, Commissioned for the exhibition Database Imaginary, 2004, Curated by Sarah Cook, Steve Dietz and Anthony Kiendl,for the Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre, Canada (and touring)What systems or processes do you use to ensure a contemporary critical teaching practice?

YoHa (Graham Harwood), Lungs-London.pl, Commissioned for the exhibition Database Imaginary, 2004, Curated by Sarah Cook, Steve Dietz and Anthony Kiendl,for the Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre, Canada (and touring)What systems or processes do you use to ensure a contemporary critical teaching practice?

I follow the artists and their work. Which means, I encourage students to interrogate what an artist has done, how and why and who for. And then I question where that reading of the work has come from: Have they been misled by patchy documentation? Did anyone record a first hand experience of the work that they could consult? Is the artist’s intent recorded anywhere? I try not to reinforce an academic hierarchy between sources, but question their authenticity, and thereby encourage students to make their own documentation. In my ‘Curating Lively Practices’ class last semester I said that no one could cite a Wikipedia page in their essays unless they’d edited the Wikipedia page themselves. I think that frightened a few, which it wasn’t meant to, it was to encourage participation in the creation of resources about art, participation in the online culture we all unthinkingly consume.

What aspects of your teaching practice do you work hard at to keep consistent and why?

Probably being approachable and slightly tangential in my thinking, drawing on my own experience and offering my own connections, memory or impression of something as a document to go test the veracity of. I show I am connected to current practice, that I have seen or attended exhibitions or talked to artists or other curators, or visited museums, or tried to keep my own papers and digital documentation in order (and failed). This means I can be understood as a practitioner constantly engaged in research, and therefore that curating is an ongoing, iterative activity.

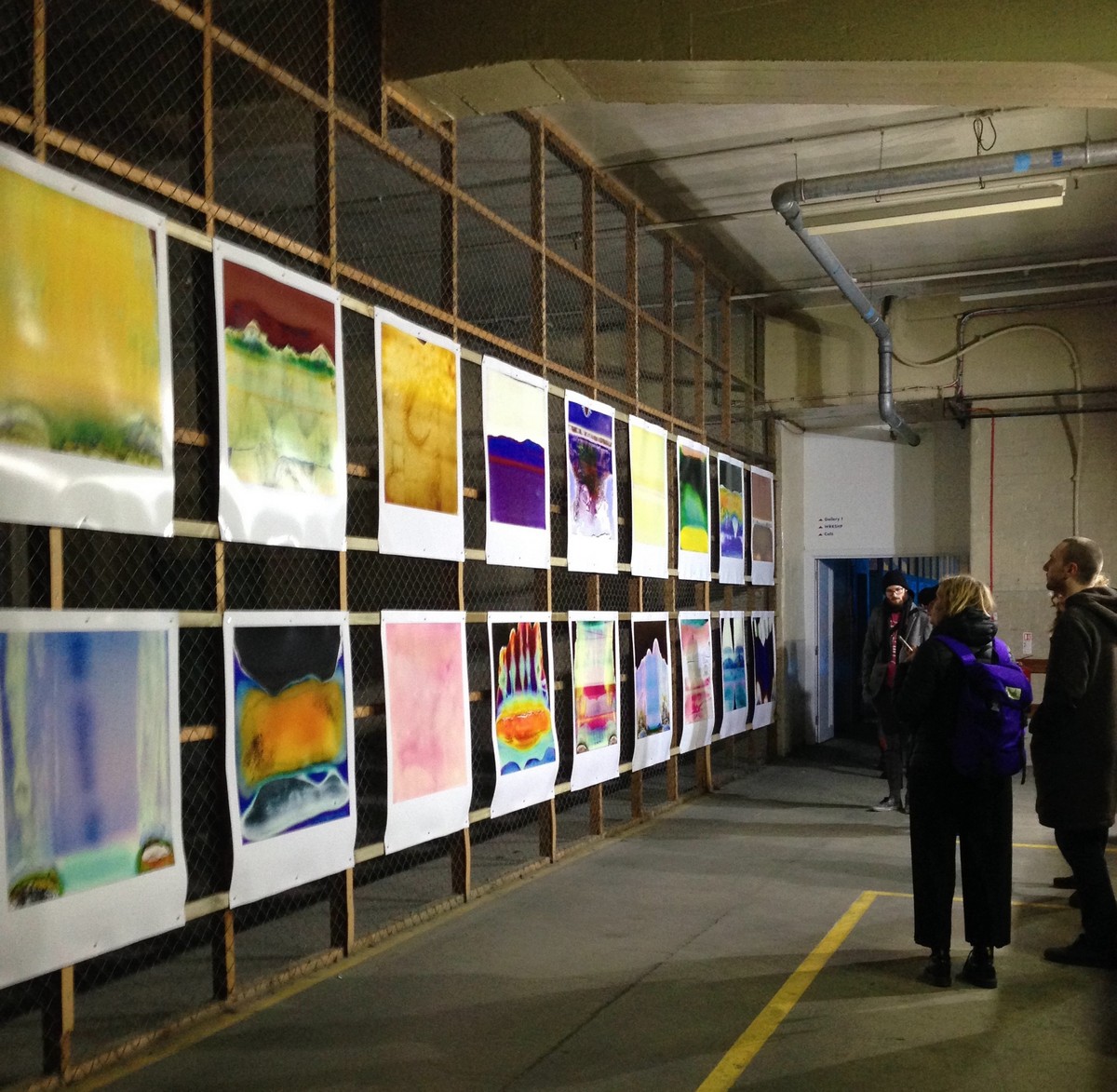

Installation view of Bill Miller, Ruined Polaroids, at NEoN Digital Arts Festival, 2017, Installed in DC Thomson’s West Ward Works, former newspaper printing facility in Dundee, as part of the curated exhibition Media Archaeologies

Installation view of Bill Miller, Ruined Polaroids, at NEoN Digital Arts Festival, 2017, Installed in DC Thomson’s West Ward Works, former newspaper printing facility in Dundee, as part of the curated exhibition Media Archaeologies

What art educators, art colleges, courses or curriculum have inspired you?

A friend who has written a book about toilets (Lezlie Lowe’s No Place to Go) was asking something about public conveniences in the UK post-pandemic, and it sent me on a deep trawl of Archive.org’s Wayback Machine to find the syllabus for a course (I didn’t take, but a friend did) at the defunct MRes/PhD programme The London Consortium (run by Tate, The AA, The ICA, The Science Museum and Birkbeck) about the history of shit and civilisation. I was reminded how much I love an idiosyncratic reading list (that combines art work, philosophical texts, historical records, museology, archival theory, sociology, film, etc.).

I think if an artist or designer wants to work with digital tools then I’d send them to the School for Poetic Computation, run by TaeYoon Choi, or Interactivos? run from Medialab Prado. Or if they want to experiment with biological materials in art I’d send them to Cultivamos Cultura in Portugal, or to Symbiotica at the University of Western Australia…There are any number of niche communities and hard working organisations out there for whatever it is an artist wants or needs to learn.

Learning from practitioners is key. I was taught by an amazing roster of curators when I was a masters student in New York last century. I particularly remember being challenged by the art critic Peter Schjeldahl to be less dashing in my disdain in my writing, and to not overthink or over-intellectualise things (still failing at that!). Dia Art Foundation curator Lynne Cooke (now at the National Gallery of Art in Washington) taught me that conversation with the artist is the most important thing – go to their studio! Diana Nemiroff, longtime curator at the National Gallery of Canada, taught me that context, facts and materials need to be properly researched and understood in order to curate, more so than (the then emerging) tomes of curatorial theory. Art historian Linda Norden taught me to follow my instinctive reading of a work down a path, articulate it. And during lockdown, a few months ago now, Canadian artist and lover of libraries, Cliff Eyland, died, and I remembered that after I’d curated a mad show about snowboard culture, he told me that my ethnographic methodology (curating outwith the bounds of my own expertise, infiltrating a scene, and trusting the experience and knowledge of others) was valid and I should continue with it. I think I have.

Nowadays I am inspired by and learn from the younger curators, curatorial assistants, exhibition producers, technicians, and digital producers that I work with, recently at Somerset House and with NEoN. At NEoN we’ve had two recent graduates from University of Glasgow’s Digital Media and Information Studies programme join us on summer placements and I’ve learned a huge amount from them, not least about digital file management!

Installation view of Braking Matter by Michel de Broin; viewing the work are artists Sascha Pohflepp and Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, whose work Yesterday’s Today was also part of the exhibition (Q.E.D., Liverpool John Moore’s University Art and Design Academy Galleries, September 2011, as part of the AND [Abandon Normal Devices] Festival.) Photo courtesy of AND Festival

Installation view of Braking Matter by Michel de Broin; viewing the work are artists Sascha Pohflepp and Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, whose work Yesterday’s Today was also part of the exhibition (Q.E.D., Liverpool John Moore’s University Art and Design Academy Galleries, September 2011, as part of the AND [Abandon Normal Devices] Festival.) Photo courtesy of AND Festival

Which contemporary artists seem to be influencing artists today and why do you think that is?

Come back to me with this question in a few week’s time after I’ve reviewed the Goldsmith’s MFA (online) degree show! I’m expecting to see work influenced by artists such as Rachel Maclean and Tai Shani (fictional+digital+persona+history+storytelling+performance+++)

What tips or exercises do you recommend to artists who have a creative block?

During lockdown I tried to chat regularly with friends who were furloughed and am still checking in with them as to how they’re staying engaged when facing uncertain job futures in the shrinking cultural sector. I think uncertainty or doubt leads to inertia, so you need a routine to fall back on (even if that involves chocolate magnum ice-creams or issues of Grazia). I was reminded of Ellie Harrison’s Artists’ Training Programme which was a spoof website but had a very good daily schedule as part of it. At the time she made it, it was related to all the work she was doing about quantifying her life, and data tracking. The schedule involves always listening to Front Row – tune in after the Archers – whether you like it or not. Routine is important to give your mind time to wander. This might not get you to make art, but it might send you off down another research path which might later become part of your work.

What current issues, themes or concerns have you noticed arising in students practice in recent times? And which philosophers, theorists, writers or thinkers are influencing students today?

Those students focused on museums are deeply concerned about expertise, authority, accessibility, transparency, ethics – who decides what gets collected, what gets shown, how it gets talked about. With Black Lives Matter and the attention to public memorials and statues, anti-racist and inclusive practices of co-creation are a key concern. In rethinking the museum I’ve also been encouraging students to think about alternative spaces where culture is produced or preserved, including digital spaces, and so that includes thinking about who owns those spaces, how they are run, what they prioritise, are they held in common?

In 1968 Jack Burnham wrote in ArtForum that we’d shifted from an object-oriented culture to a systems-oriented one, where “change emanates, not from things, but from the way things are done” —museums have evolved to recognise that culture means not just looking after things but enabling audiences to engage with those things in new ways, but the artists are still ahead, always suggesting new ways for things to be done, new systems. Perhaps now we are shifting to an (inter-species? post-human?) experience-oriented culture, change emanating from how we experience the world (and all those experiences are unique, if understood to be connected). I’m not sure if this reflects what artists are working on, but I sense a real mixing of the disciplines, an intersectionality (influenced by the writings of Rosi Braidotti, Anna Tsing, Tim Ingold, Timothy Morton, all the materialist-object-oriented-speculative-design folk, and by reading horoscopes, magic spells, tarot cards, learning other knowledge systems) whether that is across social and political discourses, environmental and ethical concerns, gender and science, personal and private or collective, historical or future-oriented… COVID-19 will be part of this too, as will the Black Lives Matter movement.

So despite not having time, I’m going to dive into yet another Slack thread about how museums are responding to lockdown, in case I can convince any of them to collect some digital art made from it..

Follow Sarah Cook on Instagram @littlecurator and Twitter @sarahecook and visit her website http://www.sarahcook.info/