We use cookies to help you navigate efficiently and perform certain functions. You will find detailed information about all cookies under each consent category below.

The cookies that are categorized as "Necessary" are stored on your browser as they are essential for enabling the basic functionalities of the site. ...

Necessary cookies are required to enable the basic features of this site, such as providing secure log-in or adjusting your consent preferences. These cookies do not store any personally identifiable data.

Functional cookies help perform certain functionalities like sharing the content of the website on social media platforms, collecting feedback, and other third-party features.

Analytical cookies are used to understand how visitors interact with the website. These cookies help provide information on metrics such as the number of visitors, bounce rate, traffic source, etc.

Performance cookies are used to understand and analyze the key performance indexes of the website which helps in delivering a better user experience for the visitors.

Advertisement cookies are used to provide visitors with customized advertisements based on the pages you visited previously and to analyze the effectiveness of the ad campaigns.

I have known Iain and Jane and been a fan of their work for over 15 years. I am continually amazed by their endless curiosity, thirst for knowledge and ability to chart new waters.

They have an incredible ability to see opportunities where others see obstacles. Whether it’s performance, curating, producing films for the cinema or TV, they are meticulous in their planning and collaborative processes, in extending themselves and others to go beyond the imaginable. They are experts at spotting and mining the real potential, interrogating identity and getting to the heart of the matter. They think big and they always deliver. Their honest answers are reflective of their preferred way of working – straight talking, rising to the occasion, enabling others.

Our work relies on meeting, talking to and collaborating with others. If anything, people are the “stuff” of our practice.

Please note this interview was first published on the Artist Mentor website during 2020.

Iain Forsyth & Jane Pollard are artists and BAFTA-nominated directors working across film, installation, performance, sound, documentary, and TV drama. Working collaboratively since meeting at Goldsmiths in the mid-nineties, their work has been exhibited around the world and is collected by museums and institutions including Tate and the Government Art Collection.

Their debut feature film, 20,000 Days on Earth, won two awards at Sundance and nominations from BAFTA and the Independent Spirit Awards. In 2015 Iain & Jane received the Douglas Hickox Award for best debut director from the British Independent Film Awards.

Iain Forsyth & Jane Pollard with Nick Cave, on the set of 20,000 Days on Earth, 2013. Production Still Amelia Troubridge

What are you doing, reading, watching or listening to now that is helping you to stay positive?

We try our best to help each other to keep things in perspective. But with all the perspective in the world, it can still be tough to stay positive. We’ve been trying Transcendental Meditation, and that’s been helping. We’re finding that TM works for us better than mindfulness. The book ‘Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity’ by David Lynch is an inspirational read.

One thing that’s been amazing to see is so many friends creating these incredible communities online. There’s Carol Morley’s #FridayFilmClub, where people watch a film at the same time and then discuss it afterwards. Sue Tilley’s life drawing classes have kept going on Facebook and Noel Fielding’s #NoelsArtClub on Instagram every Saturday 3-5pm is giving kids and adults a creative outlet. Tim Burgess’ #TimsTwitterListeningParty have taken on a momentum all their own, and Jarvis Cocker is helping the nation drift off to sleep with his #BedtimeStories on Instagram.

We don’t avoid the news as much as we’d like to, but we try to balance it with equal amounts of comedy, satire and funny cat videos.

The Dali & The Cooper, 2018, Episode in Sky’s series Urban Myths, first aired on 3rd May 2018. Directed by Iain Forsyth & Jane Pollard, featuring Noel Fielding as Alice Cooper, David Suchet as Salvador Dali, Sheila Hancock as Gala Dali and Paul Kaye as Cooper’s manager, Shep Gordon. Original score composed by Richard Hawley and Jarvis Cocker

What are you working on and how has the lockdown affected your ideas, processes and chosen medium?

The hardest part is fighting the feeling of frustration. Almost all our work has fallen away, with little promise of any of it returning anytime soon, and that’s an enormous weight on the mind. We also feel the weight of knowing full well that this long period free from many of the usual daily distractions should be an ideal time to be creative. It’s especially frustrating, as an aspect of our practice involves scriptwriting, and on paper, isolation should be the ideal time to write. But so much energy is needed just trying to stay stable and sane, that the focus isn’t there. It’s especially tough working collaboratively, as our brief periods of productivity never seem to coincide. It’s a daily challenge, but we battle on!

There’s a couple of ’strategies’ we’ve tried to implement. We’re forever making lists of films we want to watch or see again because they relate to a particular project or idea. But it’s one of those things we’ve rarely found time for. So, at the start of the lockdown, we committed to watching one film every day. The discipline of it is useful, and the 55+ films we’ve watched so far has left us feeling enriched.

Another project we’ve undertaken is using the time to take stock. We’re going through more than ten years’ worth of hard drives, making sure our masters are properly archived. Along the way, we’ve unearthed some fantastic memories. We’ve shared some of them on social media.

The World Won’t Listen, 1998, 60 minutes, Live performance featuring The Still Ills

What do you usually have or need in your studio to inspire and motivate you?

People! Our work relies on meeting, talking to and collaborating with others. If anything, people are the “stuff” of our practice. That’s what we’re missing the most right now. Sure, there are other ways to communicate. You name it, we’re using it; we’re Skyping, Zooming, hanging out in Google Hangouts, chatting on WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger, getting annoyed with Teams and even Houseparty-ing. Of course, we’re lucky to have all these options, but none of them beat being in the same room. And while it’s possible to keep talking about our work, so far, we haven’t found any way to continue actually making it.

One of our biggest inspirations is books. Our studio (and home) are full of them. But our studio is also a very practical space, with whiteboards and everything on wheels so we can quickly reconfigure. Since we moved into our studio at Somerset House, we’ve discovered that the absence of things is as important. Home is full of distractions. Oh, and cats. Same thing, really.

What systems, rituals and processes do you use to help you get into the creative zone?

In our quarter-century (bloody hell!) of working together, we’ve learnt quite a bit about the nature of creativity. We’ve been lucky enough to witness it in some remarkable people and talk to them about it.

Here’s something we know we know, something we learnt from Nick Cave. Creativity is not difficult. Anyone can do it. You can take the tiniest idea and, providing you stick with it — put the time and effort in — it will grow into something. You must do the work and trust the process.

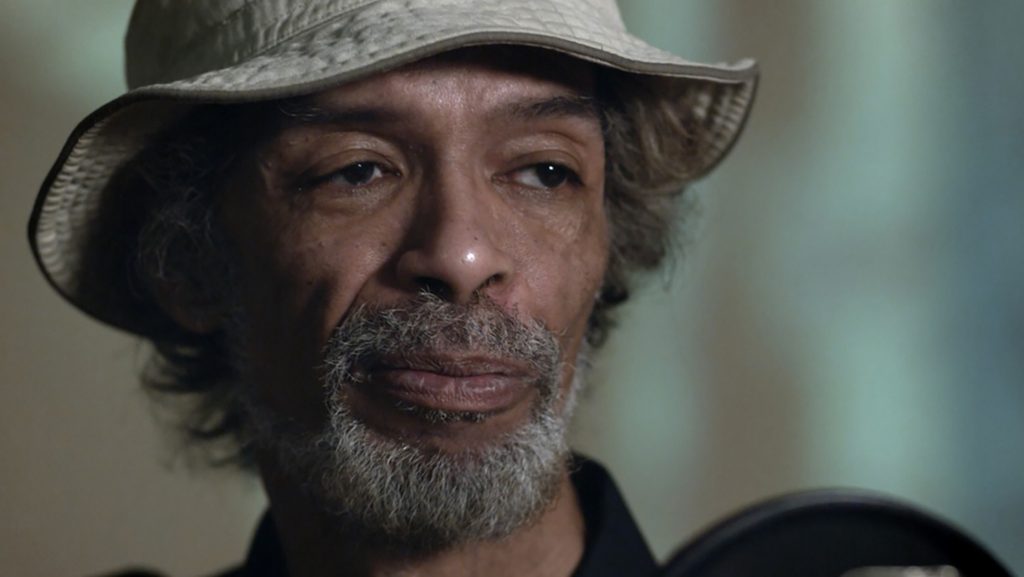

And here’s something we know we don’t know, inspired by Gil Scott-Heron. Creativity is elusive; it comes from somewhere else. Gil would say it came from ’the spirits’. The name doesn’t matter, but you do have to understand that it comes from the side. Somewhere out of view, often from the darkest corners at the back of your mind. Sometimes in the shower. Sometimes only when the fuse is lit by the creativity of others. It’s sparked by many things and will bounce hither and thither, as you try to catch it. It’s elastic, elusive and electric.

In our experience, creativity is also obstinate. It refuses to be tied to a specific ritual or circumstance. To us, creativity seems to be 90% effort, maybe 9% bloody-minded self-confidence and 1% pure magic.

Who is Gil Scott-Heron?, 2015, 60-minute feature documentary

What recurring questions do you return to in your work?

There’s a line that pretty much sums it up for us. It’s from an oft-quoted Albert Camus essay:

“When we are stripped down to a certain point, nothing leads anywhere anymore, hope and despair are equally groundless, and the whole of life can be summed up in an image. A man’s work is nothing but this slow trek to rediscover through the detours of art those two or three great and simple images in whose presence his heart first opened”.

In our film 20,000 Days on Earth, Nick Cave elegantly describes the process of song writing as chasing after “those moments when the gears of the heart really change”. And, while we’re throwing around the quotes like an art student on an essay deadline, we should also mention our fondness for these words from Rainer Maria Rilke’s ‘Letters to a Young Poet’: “Have patience with everything that remains unsolved in your heart… you need to live in the question.”

That’s what we’re trying to do; live in the question.

What do you care about?

We care about the arts. This is the stuff that we build lives around. Many of us construct our very sense of self through our relationship to arts and culture. They are a powerful tool, able to effect great change. And when the going gets tough, the arts are a lifeline. Who isn’t feeling even a little bit less isolated right now by climbing inside a book, playing great music, watching movies or playing video games? Yet as a society we seem to be giving up. We’re literally letting go of the stuff that makes us who we are. It’s a catastrophe.

In ‘Know Your Place’, his essay on class in the art world, Dan Fox puts it perfectly succinctly: “Art is for everyone, but participation in its professional systems is not.” He goes on: “I find art profoundly interesting but, despite 18 years in the business, I feel alienated by the games of hierarchy that play out around me, because they involve forms of classism that few will admit to.” It’s well worth a read in full.

DOUBLETHINK, 2018, Video installation, Sheffield Doc/Fest, Tudor Square. Photo Henry Rees

What risks have you taken in your work that paid off?

Risk is such a hard thing to talk about. There are artists who’ve taken a risk by introducing a new colour into their palette. And there’s artists who’ve taken a risk by getting themselves shot. There isn’t a ‘risk scale’ that makes any sense to draw comparisons.

Likewise, how do we quantify whether a risk has ‘paid off?’ In our minds, it only makes sense to talk about risk if there’s something genuinely at stake. Maybe if you’ve built a commercially successful practice by doing one particular thing, then anything that deviates from that is a risk to your steady source of income. But because we’ve never had that, we’ve never had to face those sorts of risks.

For sure we’ve taken chances. We’ve borrowed money to make up shortfalls in project budgets. We once completely changed a proposal that had been agreed by a museum, and somehow managed to convince them to come with us on a completely different creative journey. Sometimes you get lucky, sometimes it backfires. But artmaking should be a process of constantly taking creative risks. Without that, what’s the point?

What risks have you taken that perhaps did not go so well but you learnt the most from?

When things haven’t gone well, it’s usually because we’ve pushed things too far. But we feel duty-bound to do this. Maybe if our practice had evolved with a specialisation, we’d feel different. But our interest is in what it’s possible to achieve as an artist. That means we’re always going to try to break things.

Probably the first time we understood the value of this was while we were making a series of live art projects in the nineties. With one project, we found the breaking point for that set of ideas. But by being pushed to confront failure we were able (eventually) to reformulate that strand of our work into what became our biggest and most successful live project. Perhaps it’s too much to say it would never have happened without the earlier mistakes, but it was absolutely better for what we’d learnt along the way.

Such a mixed practice has given us an amazing range of experiences, even if we’ve learnt it’s a hard way to make a living. We’ve worked with live performance, directing film and television, video editing, scriptwriting, curation, sound installations, collaborated with musicians, writers, actors, technologists, scientists, even magicians. And although what we choose to experiment with frequent changes, we enter each project with the same heads, minds, and hearts. For us, that’s what being an artist is all about.

Silent Sound, Installation view and performance, St. George’s Hall, Liverpool, 2006/7

What is your favourite exhibition, event, or performance you have participated in and why?

Like children (so we’re told) it’s hard to pick a favourite. But the projects we enjoy the most are invariably the ones that scare us the most. Fear is important, it’s the fuel in the tank.

Silent Sound, a live performance and installation we made in Liverpool in 2006. It was the first time those two sides of our practice came together, with the gallery component of the piece created, quite literally, overnight. This was also the first (and to date only) project which involved us personally performing. Aside from the huge adrenaline rush, the work also felt like it was entering new territory for us. A lot of subtle psychological trickery went into a piece that was ultimately rather honest and exposing.

It would be impossible not to also mention 20,000 Days on Earth. This film allowed us to work through so many experiments. It was making this that we met the cinematographer Erik Wilson, who we continue to work with. He’s truly inspirational. And of course, the film has opened doors to projects we would have previously never been able to realise. So, it’s very dear to us.

20,000 Days on Earth, 2014, Feature film, 97 minutes, Production Still Amelia Troubridge

What would you hope that people experience from encountering your work?

Put simply, we want to make work that can make someone else feel the way we have felt in the presence of transformative objects and experiences. We want our work to have an immediate effect and leave a lasting impression.

Could you tell us a bit more about at a time when you felt stuck and what you did to help yourself out of it?

Whenever someone badly lets us down it throws us off our tracks. When you’ve put so much of yourself into a project, it can hit hard. We’ve been in some real ruts over the years. It’s rare, but when it happens, it’s the most anti-creative situation we’ve ever found ourselves in.

There’s something debilitating about feeling like you have no control over anything anymore. And that creates a completely different kind of crippling fear. It’s tough to claw your way back from feeling so powerless.

Very early in our career, we did a project with an ‘artist-run’ space. We’d agreed to split the costs of making the work 50/50. But when the bills started coming in, the gallery always had a reason why they couldn’t pay their share. We scraped by and borrowed money to clear the debts, hoping their contribution would eventually come through. It never did. For a pair of baby artists, just finding their way in the world, that was so destructive. To this day, we find ourselves occasionally being unhelpfully distrustful in a way that we know traces straight back to that experience.

There’s no sure-fire fix that we’ve been able to find. In time, you dust yourself off and start to try things. Play. Fail. Daydream a little. Slowly you being to bounce ideas off other people. And bit by bit, you become unstuck.

Doublethink, 2018, Two screen video installation (15 mins, looped), Filmed at Somerset House Studios, London

What kind of studio visits, conversations or meetings with curators, producers, writers, press, gallerists, or collectors do you enjoy or get the most out of?

The best visitors are those that bring a cheque book! (Sorry, not sorry.)

Okay, flippant answers aside, the best meetings and studio visits are with those who can push you beyond the things you usually say. Those stock phrases you collect about your work that act as a crutch when you’re forced to talk about it. We’ve never believed that we’re the experts on the theory surrounding our work. We know what we’re trying to do or say, but that doesn’t mean we’re succeeding.

Listening to someone you trust completely tell you something you never realised about what you do is incredible because with this new insight we’re able to progress, refine or change what we’re doing.

If someone enters a dialogue with an open mind and an open heart, we will get along just fine. We give a lot of ourselves when we meet people, and it’s rewarding when that’s given back.

Multigraph 013 (Paul Kaye), 2018, C Type Fuji Flex, 32.5 x 48 x 3.5cm (framed), Edition of 3

If you work with a commercial gallery how does this relationship affect or inform your work and life?

We are represented by a commercial gallery (Kate Macgarry), and we have a manager/agent who looks after our film and TV projects. Working with a gallery has helped get our work placed in museums and public collections, but we’ve never really found our feet with private collectors. We know we’re not an easy fit for the art market. But as much as we wish that wasn’t the case, making work that tries to chase the market just isn’t for us.

We’re never been an easy fit in any of the industries that we have worked in. We tend to operate in a way that never quite fits the models for success. Despite their often-modest budgets, we find institutions are a good setting for us because our ambitions tend to align. We are always interested in bringing new and diverse audiences in to experience our work.

With film and TV becoming part of what we do, we now have a manager. He is a brilliant sounding board. Someone who will always tell it to us straight, even when it is not easy to listen to. Maybe because film and TV are inherently collaborative mediums, we have found that world a little easier to navigate. So much of the art world seems to go on behind closed doors, or at least doors we have never learnt how to open. We haven’t made things easy for ourselves.

Poster for File Under Sacred Music, 2003, single channel video, 22 mins

Do you have a trusted muse, mentor, network, or circle of friends you consult for critical feedback?

In 1993 at ‘A Fete Worse than Death’ we met Joshua Compston. He became the closest thing to a mentor we’ve ever had. We would meet most Sunday mornings in Shoreditch and tape record our conversations. These blew our minds wide open. Joshua wanted us to document his ideas, but we became hooked on his self-belief and the scale of his ambition. His ventures were a heady mix of brilliance and bullshit, but he taught us more in the short time before his death than anyone else.

Since then, there’s not been a single figure, although certain individuals at different times have been important to us. For example, the body of live work we produced early in our career would have been impossible without Vivienne Gaskin, who at the time was Director of Live Arts at the ICA.

Being two people means we have an inbuilt, and constant, level of self-criticism. We know two sets of instincts are better than one. And when they naturally align, we know we’re onto something worthwhile. But for us that only works at a project level. Regrettably, we’ve never been able to apply those instincts to any sort of career strategy.

Things are a little different in film. The art world seems so firmly bought into the idea of the autonomy of the artist that it seems to be only after something has been completed that people step forward to tell you what they think of it. Producers and executive producers in film are always able to be consulted during the making process. Most of the time, that’s a good thing! Maybe commercial galleries can provide that for some artists, but we’ve never had those kinds of relationships in the art world.

Our friends are brilliant — always open to reading a script we’re developing or watching a rough cut of something. So, there’s a handful of people we return to when we need an outside voice.

Bish Bosch: Ambisymphonic (with Scott Walker), 2013, 25 minutes, Ambisonic sound installation, Sydney Opera House for Vivid Festival

Which artists or creatives do you feel you are work is in conversation with?

To be honest, we have never thought of our work in that way. Even some of the pieces we have made that very directly riff on existing artwork, such as ‘Walking After Acconci’, were never about a conversation with the original artist. It’s the dialogue with an audience that’s important to us.

Of course, there’s a sense in which all our work is in conversation with fellow creatives. That might be the more subtle collaborations that take place between us and, say, a cinematographer. Or sometimes the collaboration is more overt, such as the project we made with Scott Walker for Sydney Opera House. These real and direct conversations are incredibly important to us and our work.

Kiss My Nauman (still), 2007, 4 channel HDV projection, silent, duration: 47 mins

How do you make money to support your practice?

It’s rarely talked about, but one of the most difficult things is that the projects we’re best suited to are usually larger scale, working with public spaces. Even when the budget to realise the work is there, it rarely covers the true time, effort, and resources that the project requires. As the artist, you’re expected to be the most committed person in the room. We have no problem with that, we work stupidly long hours every single day. But when everyone around you is on a salary and your artist fee isn’t covering even close to minimum wage, it’s tough.

There’s such a strong sense in this country that the arts are a luxury, and that if you don’t have a private income to support yourself, then you should go and do something else. How do we even begin to fix that?

For almost twenty years, we supported our practice with part-time jobs. Initially in the book trade then, for 12 years in the record industry. We weren’t able to fully reshape our working life until after the success of our first feature film. Although it brought us little in the way of hard cash, the doors opened have been immense. We’ve been able to incorporate film and TV work into our practice. As glamorous as this perhaps sounds, we’re only able to take on a small amount. It’s gruelling work, and we’re not right for the sort of conventional projects that enable directors-for-hire to make a good living.

So, there’s still no single or solid source of income in our life. We try to keep enough plates spinning in the hope that some eventually pay off. We’ve never liked the lack of transparency in the art world, so let us put our money where our mouth is and give you an idea of how we’ve made money over the past year.

It’s been a real mix: Small development fees for scripted projects that may never move beyond development; some income for work on a Nick Cave exhibition which was due to open in Copenhagen but is now on hold; a percentage of the anticipated income for co-curating an exhibition that has now been postponed; tiny amounts from royalties and image licensing; an executive producer fee for mentoring a friend through the process of directing her first feature documentary.

Other than that, there may be an occasional modest fee for a mentoring day or something similar, but it’s shaky. And we’re now seriously concerned about making it through this year and the current pandemic, as we fall through the cracks of almost all Government support.

David Suchet as Salvador Dali in The Dali & The Cooper, 2018

What compromises have you made to sustain your practice?

We haven’t pursued creating a family. it has never felt financially viable, and we don’t have the first clue how we would navigate that as well as working as a collaboration. Around us, we’ve built up the most wonderful community of friends and peers, who we value immensely. Perhaps this is our compensation for not having a larger family of our own.

We work incredibly long hours, typically 12 hours a day, and always 6 days a week. More when we need to. It’s the only way to fit everything in, especially when juggling part-time job commitments.

We’ve compromised ourselves financially in every way imaginable. Everything that comes in, goes back into the work. We’ve had one ‘holiday’ in the last 25 years. Don’t get us wrong, that isn’t meant as a sob story. We’re incredibly lucky to be able to travel often with our work, and we’ve often tagged days off onto the end of a work trip. But there’s no doubt we could’ve had a better standard of living with a more conventional choice of career.

What advice would you give your past self?

Oh, we’d have been far too stubborn to listen. Worry less, maybe.

Something we’d love to have understood sooner is this, a quote from Italian physicist Carlo Rovelli “The best grammar for thinking about the world is that of change, not of permanence. Not of being, but of becoming.”

Sheila Hancock as Gala Dali in The Dali & The Cooper, 2018

Can you recommend a book film or podcast that you have been inspired by that transformed your thinking?

It’s attitudes we fall for. Anyone who refuses to accept there’s a way things ought to be. But it’s a kind of alchemy, you have to be an active element in the inspiration equation.

Two books we’d heartily recommend are ‘Lanny’ by Max Porter and ‘Waiting for the Last Bus’ by the Right Rev. Richard Holloway. The Two Shot Podcast hosted by actor Craig Parkinson is a wonderful series of brutally honest conversations, mostly with actors, but they reveal so much about creativity.

The films we return to most often are ‘F for Fake’ by Orson Welles and ‘O Lucky Man!’ by Lindsay Anderson. Both have been transformational.

Visit Iain and Jane’s website and find them on socials @iainandjane and at Kate Macgarry.

All images c/o the artists and Kate Macgarry