I first met Eleanor Moreton in 2007, when she was Durham Cathedral Artist in Residence.

I knew before we met that I loved and connected with her paintings, but during that first meeting I was also struck by her curiosity, playful sense of humour, delight in the absurd, and her unwavering commitment to challenging the status quo.

I have been lucky enough to have many rewarding discussions since with Eleanor, during studio visits and in making exhibitions together. I relish our conversations, as she peppers them with references to music, philosophy, poetry, European history, and reveals brilliant insights into other artists work. She is one of the most interesting and interested artists I know.

There are many times when I've tried to make paintings and they have gone under, swamped by over-working and, perhaps, under-preparation. But nothing is lost. Nearly every painting is a learning experience.''

Please note this interview was first published on the Artist Mentor website during 2020.

Her work is informed by this wide-ranging research and a passion for developing new skills. When she’s not painting, she’s reading, playing or performing on the violin, dancing, meditating, cooking or caring for friends.

Her rich, multifaceted paintings reflect her highly attuned ability to conjure yet simultaneously deconstruct the subject, the surface, the frame; seducing the viewer yet rejecting the possibility of allowing them to soak up the sun for too long. Eleanor reveals the power at play, the beauty and the horror of our questionable relations. She is always unflinchingly honest.

Eleanor Moreton is a painter who lives in London. She studied painting at Exeter College of Art (BA), Chelsea School of Art (MA), and Art History at the University of Central England (MA).

Her most recent solo show was Wodewose, at Arusha Gallery in Edinburgh, 2019. Previous solo shows include A Cold Wind From The Mountains, Exeter Phoenix, Exeter, 2017; Monro Room, The House of St Barnabas, London, 2016; California Dreaming, Canal, London, 2015; Tales of Love and Darkness, Ceri Hand Gallery, London, 2014; I See the Bones in the River, Ceri Hand Gallery, London, 2012 (reviewed in Art Monthly by Peter Suchin); The Ladies of Shalott, Jack Hanley Gallery, New York, (reviewed in Art in America by Julian Kreimer), 2010; Im Wartezimmer, Ceri Hand Gallery, Liverpool, (reviewed by Jonathan Griffin, Interface, and Robert Clark, The Guardian, 2010) touring to The Terrace Gallery, Harewood House, Leeds, 2010; A Buried Life, Reg Vardy Gallery, Sunderland, (reviewed by Robert Rob Clark, The Guardian, 2008; Eleanor Moreton Paintings, DLI, Durham, 2008.

Key group exhibitions include The Classical, Transition Gallery, London; Sampler, Arcade Fine Arts, London, 2017; Liberties, The Exchange, Penzance, and Collyer Bristow, London, 2016, with Helen Chadwick, Rose English, Hayley Newman and Jo Spence.

Her work can be seen in The Anomie Review of Contemporary British Painting by Matt Price, (Anomie, 2018) and Picturing People by Charlotte Mullins, (Thames and Hudson , 2015). She has participated in art fairs including Frieze Art Fair, London, Art Rotterdam, NADA Miami, The Armory Show, New York, VOLTA, Basel and Manchester Contemporary.

The Way (entering the meadow of certainty), 2019, Oil on canvas, 170 x 210 cms

What are you doing, reading, watching or listening to now that is helping you to stay positive?

I decided I would try and use the time as a sort of retreat, to pause and reflect on my life. Tending my garden, cycling around Wanstead Flats have kept me cheerful, and nice chats with friends and neighbours.

What are you working on and how has the lockdown affected your ideas, processes and chosen medium?

The real way that Covid19 and lockdown have affected my work is in a sense of compression and intensity. The lack of distraction has reminded me of long periods in my life when I buried myself in my work. Whilst I wouldn’t choose to do that now, it does have a calming effect, because making art is one thing you can do, one place you can be, where you can affect change.

The frustrations and complexities of relationships are on hold, which, though sad, has been restful.

I don’t know whether this is related to lockdown, but I’ve being trying out working on unprimed canvas. Perhaps lockdown gave me a container to do that. And maybe there’s a sense of distance too, so it feels possible to stand back and assess where things are going in my work.

The Family Wood, 2018, Oil on canvas, 90 x 120 cms

What do you usually have or need in your studio to inspire and motivate you?

I need to be warm and I need a teapot (with tea in it); all my materials around me, a chair, a wall and writing paper.

What systems, rituals and processes do you use to help you get into the creative zone?

I have a mantra that anything goes in my studio. I can work, or I can not work. It is a space of possibility and not of obligation or duty. I do what I feel like doing. It must be pleasurable, if I want to spend time in it and freedom is what gives me pleasure.

What recurring questions do you return to in your work?

What a challenging question! My work is very closely connected to my inner life. So recurring questions are ‘Why am I the way I am?’, ‘Why are they the way they are?’, ‘Why are things the way they are?’.

I recognise that I am fascinated by what in previous eras would have been called Evil and by those who get pulled into its orbit. Hence paintings about Charles Manson, murderers, Bluebeard, Josef Fritzl. I am interested in sexuality and repression, masculinity, and femininity. Whilst there is a strong psychological component in my work, I don’t take one theoretical position. In fact, my work is an attempt to get away from theoretical positions. Painting for me has been about moving the activities of the mind into the body.

The Murderers, 2016, Oil on canvas, 76 x 81 cms

What do you care about?

I was brought up a vegetarian when nobody else was, which was awkward. Children’s parties where I was afraid to eat in case I inadvertently ate meat. So I always had this horror of killing animals. I find I am getting more and more upset by the way we try to dominate the natural world.

I care about the position of girls and women in many parts of the world. I would like to see an end to FGM.

What risks have you taken in your work that paid off?

I can’t think of any! Perhaps because I don’t think there are any real risks in making artwork, unless you make something that falls on someone’s head. That is one of the amazing things about art. You can do anything because no one’s going to die (well there are a few instances where people have voluntarily made that their area of investigation). And I can’t really think of anything I have done which I could say paid off either.

Hole, 2019, Oil on Canvas, 35 x 30 cms

What risks have you taken that perhaps did not go so well but you learnt the most from?

There are many times when I’ve tried to make paintings and they have gone under, swamped by over-working and, perhaps, under-preparation. But nothing is lost. Nearly every painting is a learning experience.

I think there is something about contemporary painting which is, and should be, quite humble. I don’t think a painting has been made that is riskier than Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon, and that was made more than a century ago. That was an amazing era when painting was clearly taking the obvious risks and adventures. I think the risks we take now are subtle, psychological, philosophical. Painters know we’re not considered at the cutting edge in the art world. Yet we still do it. In my view, the risk and the challenge are to go, possibly quietly, into the absurd and the incomprehensible.

Toad, 2019, Oil on canvas, 50 x 45 cms

What is your favourite exhibition you have participated in and why?

I mostly love being in group shows and the moment when you have finished hanging a solo show is fantastic. I have to say though that it’s really all over then. I don’t really enjoy Private Views.

But I do absolutely love performing on stage with John Hegley: a high point for me was a late spot at Latitude with a big audience, many of whom had flowers in their hair. Another was at the Udderbelly Festival on the Southbank, in a beautiful venue, rather like an old music hall, joined by Diego Brown and the Good Fairy. More recently in a cabaret at the Wanstead Tap, with the fantastic Frank Chickens topping the bill.

What would you hope that people experience from encountering your work?

What stage performing with John has shown me is how joy can be spread and how humour can bring brief respite to our lives. I think this is profound and humbling.

Of all the visual arts, I think painting has the most power to touch us in a deep, complex, non-literal way (of course I would think that!). I can think of a few painters who succeed in this, but it’s rare. I would like to touch people in that way although I don’t think I’m there yet. Writing this reminds me to focus on that aim.

Shopping, 2019, Oil on Canvas, 50 x 40 cms

Could you tell us a bit more about at a time when you felt stuck and what you did to help yourself out of it?

When I was at Chelsea doing my MA, my father died, and I found myself blank. On the advice of my tutor, I went out with a video camera with a very open mind, curiosity, no agenda.

When that sense of lack happens to me now I’m very gentle with myself, and gentle with my work.

When I’m stuck struggling with a particular painting, that’s a different thing. I work on many paintings at the same time and when one is proving difficult, I just put it out of sight and work on another. At some point you’ll take the original painting by surprise and know what needs to be done.

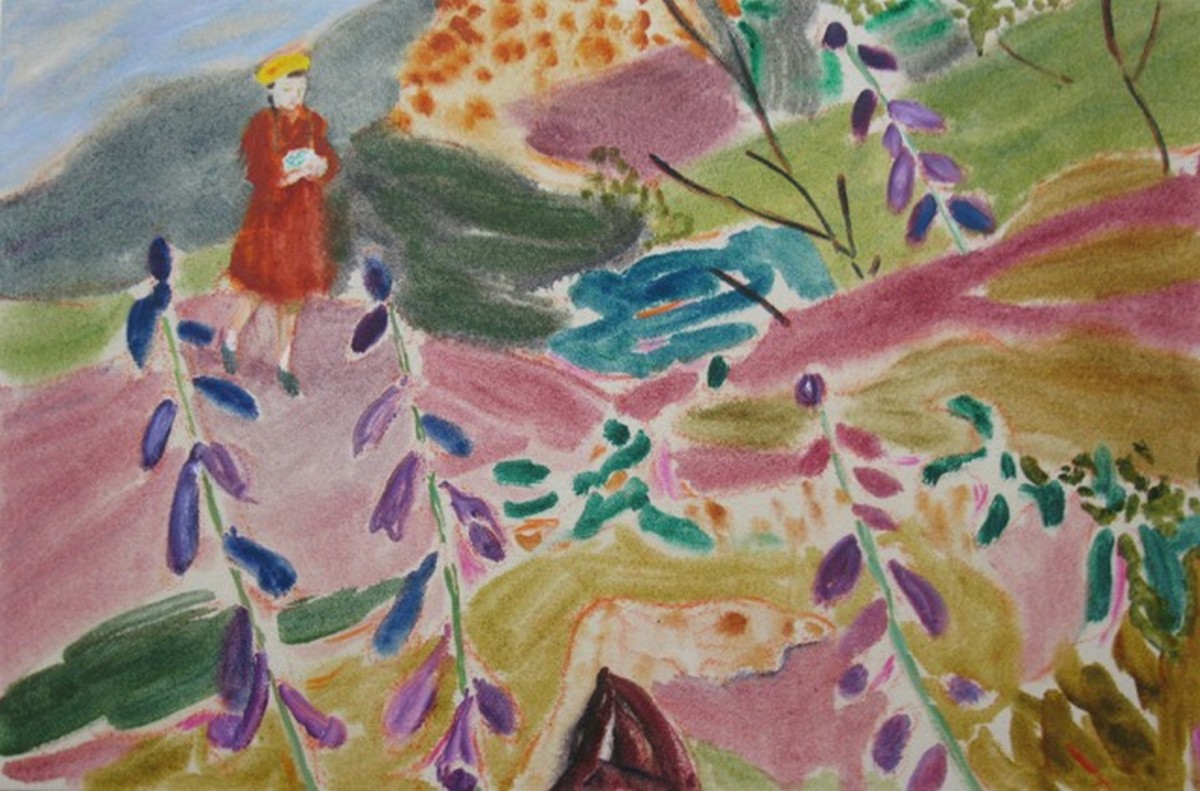

Walking, 2019, Oil on Canvas, 45 x 35 cms

What kind of studio visits, conversations or meetings with curators, producers, writers, press, gallerists, or collectors do you enjoy or get the most out of?

I don’t get many conversations and I’m always curious about what people say. I like to hear the positive and the negative because it’s all useful. It’s always good to see Rosalind Davis from Collyer Bristow, Agnieszka Prendota from Arusha Gallery, yourself, and Monika Bobinska who ran Canal.

Do you have a trusted muse, mentor, network, or circle of friends you consult for critical feedback?

Yes, but very few! The relationship must be very trusting for me to know I’m hearing their truth and for them to feel safe to tell it.

Which artists or creatives do you feel your work is in conversation with?

That’s very difficult. There are painters whom I admire and feel a connection to, like Mama Andersson, Jochim Nordstrom, Hernon Bas, Michael Armitage. There are photographers like Stan Douglas who resonate. They are all image makers and storytellers. However, these are only one-way conversations. Amongst my peers, I would say there are various low-key painterly (and personal) conversations going on, between me and Cathy Lomax, Jacqueline Utley, Jeff Dennis, Greg Rook, John Campbell, and Freya Douglas Morris – and others.

The Hunting of the Wodewose 3, 2020, Oil on canvas, 52 x 80 cms

How do you make money to support your practice?

I’ve done many things: lecturing, admin, cleaning. I was a PA in the House of Lords for a year, I worked at the Institute of Psychiatry, interviewing Alzheimer’s carers another year. Most recently I worked in the finance department for the studio providers, Acme. To be honest, I gave up lecturing because it was so hard to get. I needed to make money and took the path of least resistance.

What compromises have you made to sustain your practice?

I think the compromises early on were huge. I did meaningless, unsatisfying work, so I was very poor; I put my personal life second. I stayed in unhealthy relationships, I didn’t even consider whether I could have a family. I didn’t expect to have very much, and I think at times life was much bleaker than most people outside the art world would tolerate. For quite a long time I blamed my practice for this, but now I can see the bigger picture better.

What advice would you give your past self?

Believe in yourself. Be brave, be seen.

Gift 2, 2020, Oil on canvas, 52 x 80 cms

Can you recommend a book, film, or podcast that you have been inspired by that transformed you’re thinking?

In painting, I think finding the work of Karen Kilimnik was transformative. I was brought up to over-invest in logical thinking and I tended to try and think my way through painting. In Karen’s work I saw the kind of dreaming and fantasy which was natural to me, but which I hadn’t realised was allowed. I was for a long time very hidebound by what I thought was allowed. After that, painting stopped being painful.

A book that was transformative would be Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s ‘Shambhala – The Sacred Path of The Warrior’. It was my introduction to the practice of Tibetan Buddhism.

Follow Eleanor @eleanor_moreton or visit www.eleanormoreton.co.uk