I first met Christian Viveros-Fauné in 2004, when I was Director of Exhibitions at FACT in Liverpool and we were launching Bjørn Melhus’ first UK solo show. Christian represented Bjørn at the time through his gallery, Roebling Hall, (based in Brooklyn, New York).

At dinner together, with Bjørn’s German Gallerist, Anita Beckers, I was struck by Christian’s mischievous playfulness, his passion for art and social justice, his distrust of the mainstream and delight in discussing political issues intertwined with pop-nonsense over a glass of wine or two.

We share an allergy to artworld baloney, enabling as many people as possible to experience culture and for having fun along the way. Christian has donned many arty hats and remains consistently curious, committed to artists and is a fervent believer in the power of the arts.

I workshop my ideas by putting them down on paper; that’s how I make connections, contemporaneously, art historically, socially, politically, but also with an eye to the culture at large. I am nothing if not a big believer in making exhibitions that widen access to visual art.''

Please note this interview was first published on the Artist Mentor website during 2020.

I kept in touch with Christian, visiting his gallery in NYC, participating in international art fairs together, (including one he was running, VOLTA). In 2010 I invited him to curate an exhibition at my gallery in Liverpool, which he playfully titled Spasticus Artisticus. Christian and Jota Castro produced an accompanying catalogue (thanks to Jota’s generosity) and an after-show performance by French all-girl punk band, Furious Golden Shower, at my friend Natalie Haywood’s café-bar LEAF. The brilliantly shambolic gig included several annihilated, nearly naked male curators. They strutted in heels, feather boas and manky pants, provoking and titillating the crowd, reeling, and writhing as go-go dancers gone wrong. The peculiar punk cocktail was exhilarating yet revealed a distant, prudish art crowd, who seemed to find it rubber-neckingly torturous. I think the wicked joy Christian and I derive from flouting the rules that bind us may cement our friendship.

Christian Viveros-Fauné (Santiago, 1965) has worked as a gallerist, art fair director, art critic and curator since 1994. He was awarded Kennedy Family Visiting Fellowship in 2018, a Creative Capital/Warhol Foundation Grant for short-form arts writing in 2009, named Art Critic in Residence at the Bronx Museum in 2011, and has lectured at Yale University, Pratt Institute, and Amsterdam’s Gerrit Rietveld Academie. Viveros-Fauné is Chief Critic for Artland and writes regularly for ArtReview; Sotheby’s/Art Agency Partners’s in other words and The Art Newspaper. He presently serves as Curator-at-Large at the University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum and Visiting Critic at the NYU Steinhardt Department of Art and Education. He has curated numerous museum exhibitions around the world and is the author of several books. His most recent, Social Forms: A Short History of Political Art, was published by David Zwirner Books in 2018.

What are you doing, reading, watching or listening to now that is helping you to stay positive?

Not sure I’m doing anything with a view to staying positive, since I’m finding “positivity” a bit elusive these days, but I am doing a fair bit of reading on what I think are genuinely pressing concerns. Among the books I’m head-down into are David Wallace-Wells’ The Uninhabitable Earth, a recent bestseller about global warming; Sarah M. Broom’s The Yellow House, a memoir of growing up Black in New Orleans; Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns, a history of America’s Great Migration (the movement of six million African-Americans from the rural South to the industrialized North); José Luis Alonso Marchante’s Menéndez: King of Patagonia, a history of conquest and genocide in Chile and Argentina; and Francisco de Goya’s collected Letters to Martín Zapater. The worse things get, the more I turn to Goya, whom I consider to be an amazingly astute philosopher of the visual, as deep or deeper than anything the French and German Enlightenment produced. One historian wrote that, had Goya been born in Germany, he would have given Hegel a run for his money as a man of letters. The fact that he was born in Southern Europe kept him away from the habits but also the pitfalls of systematizing rationality. Another silver lining: Goya arrived at a critique of instrumental reason predating the Frankfurt School’s Dialectic of Enlightenment by 150 years. What is Goya’s The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters if not that? I derive genuine optimism from the idea that thinking generously, like Goya did, produces salutary patterns of critical thinking that we can all fall back on at perilous times like these.

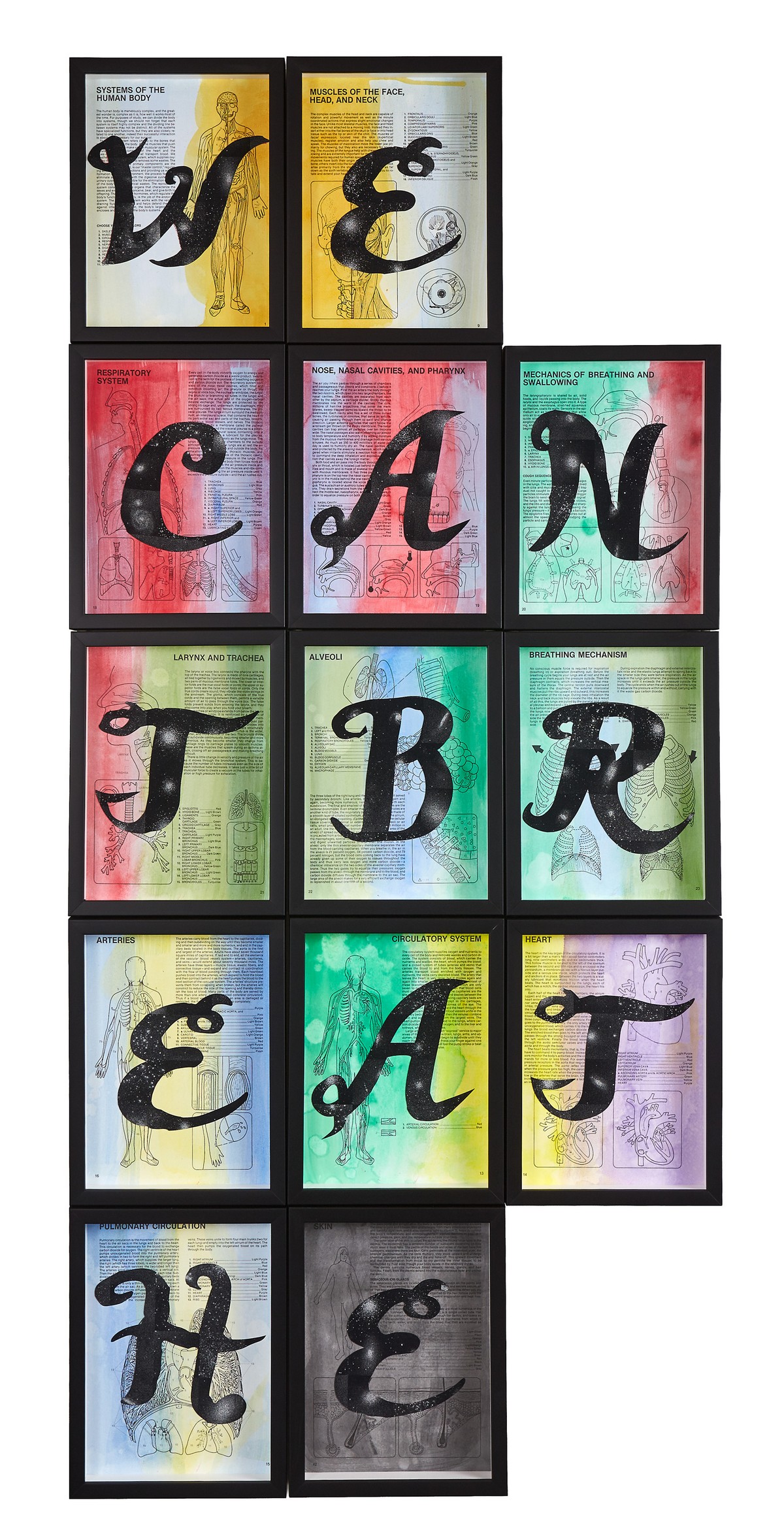

William Villalongo, We Can’t Breathe, 2015. Silkscreen on velour paper mounted on coloring book pages with acrylic wash. 12 x 9 in. each / 60 x 27 in. overall (30.48 x 22.86 cm each / 152.4 x 68.58 cm overall). Courtesy of ©Villalongo Studio LLC and Susan Inglett Gallery, NYC. Photo by Argenis Apolinario, NYC. Featured in Life During Wartime: Art in the Age of Coronavirus, University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum lifeduringwartimeexhibition.org

What are your core values and drivers that you bring to your curatorial work? What do you care about?

I care about beauty, expansively understood. Rather than being the last refuge of conservative aesthetics, the beautiful promotes thoughtful attention to the particular, to difference, as well as to comparisons that, in their fullness, require both contextual and historical study. To quote Elaine Scarry quoting Iris Murdoch “beauty prepares us for justice.” Since social justice and the expansion of civic engagement through the arts is something I am passionate about, I find myself, year in and year out, pushing for formally resolved art that engages the world—“eye candy with content” or “brain-candy with content,” in the case of conceptual art. Beauty, generously considered, doesn’t just embrace every possible art form and medium—from painting to comics to performance and social practice—it also encourages a radically egalitarian ideal, much as math and astrophysics do. Though the humanities have stupidly shelved discussions of “the beautiful” and “simplicity,” these are categories that are still discussed in leading laboratories to important scientific and egalitarian effect.

Cristina Lucas, La Anarquista (The Anarchist), from the series The Old Order, 2004. Courtesy of the artist.

Featured in Life During Wartime: Art in the Age of Coronavirus, University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum lifeduringwartimeexhibition.org

How do you develop your curatorial ideas? How do you test or scope your ideas?

I have a few basic ideas I go to the well for again and again. They include, as mentioned, curatorial takes on art and politics, but also discussions of the beautiful, though for me these notions remain indissolubly linked. Both ideas cohere for me in the concept of “social forms,” which, not so accidentally, is the title of my last book (Social Forms: A Short History of Art and Politics, David Zwirner Books, 2018). The best way I find to develop specific curatorial ideas from these concerns is to write them out. My training as a writer basically forces me to do that, so no surprise there. I workshop my ideas by putting them down on paper; that’s how I make connections, contemporaneously, art historically, socially, politically, but also with an eye to the culture at large. I am nothing if not a big believer in making exhibitions that widen access to visual art.

Gran Sur: Chilean Contemporary Art from the Engel Collection, Installation view, Alcalá 31, Madrid, Spain, 2020

How do you discover artists and what makes you finally decide you want to work with an artist?

Sometimes I find artists; other times they find me. Our meetings are always a melding of the minds, even when I’m helping put together historical shows or a biennial. For the latter, I insist of having enough work—at least three or four examples from an artist’s production—to get as complete a sense as possible of the artist’s oeuvre. As much as I value my job, I reject the idea of the curator’s authorial voice. Exhibitions, perforce, are collaborations, even when someone is appointed chef d’oeuvre. I’ve been lucky enough to work with a number of artists repeatedly. Together we arrive at ways of materializing mutual concerns, so that artworks, though properly thematized, are never reducible to my ideas. What I’m saying here seems obvious enough, but in practice I find that both experts and laypeople often get it wrong.

How do you gauge which artists and artworks will be interesting to audiences?

Curators have a responsibility to read their audiences. They do this not just to give the public what they want, but hopefully to expand and even test their audiences. Pushing the limits on what an art public wants, or says they want, is akin to what artists do for curators and critics. Surprise—an experience I’ve found to be in increasingly short supply—is as fundamental to art audiences as it is for experts in the field. Art should aspire to the condition of eternal surprise. To quote one mid-20th century proto-curator, art is news that stays news.

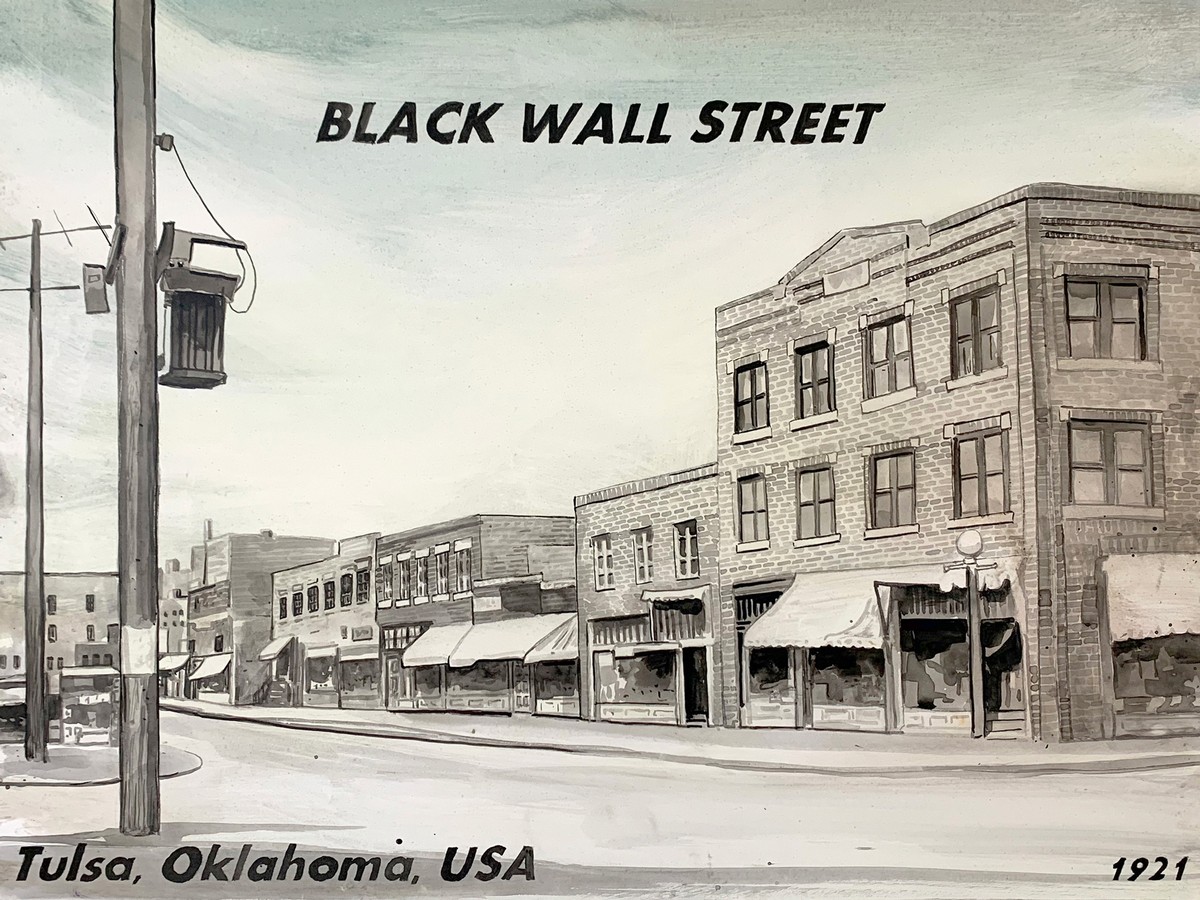

Ellen Harvey, The Disappointed Tourist: Black Wall Street, 2020. Oil and acrylic on Gessoboard, 18 x 24 in (45.7 x 61 cm). Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Ellen Harvey

Featured in Life During Wartime: Art in the Age of Coronavirus, University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum lifeduringwartimeexhibition.org

What do you offer or provide artists in the curatorial relationship?

The best artist-curator relationships are ones that develop over time. They are friendships forged through the joint public performance of shared ideas. I say performance because the making of artworks and their attendant concepts, planning, texts, supports, logistics, installations, educational missions, etc., are just some of the things that go into making successful exhibitions. The nature of an art exhibition is highly performative. Curators, in that sense, function as the producers for the artist’s solo (or group) act, setting the stage for the best live performance ever. Often, those same producers, read curators, have also had a hand in shaping the artist’s songbook.

Can you describe what you ideally want to achieve when curating an exhibition?

The best exhibitions I’ve been involved in push the envelope on the envelope; by which I mean that they reinterpret the brief of the exhibition and the physical contours of the space it occupies. Sometimes that involves getting a genuinely novel read on a set of given artworks or a historical period; at others it involves expanding the physical possibilities of a gallery, a building or public space. At the best of times you get to—or are forced by circumstances—to do both. In my experience, those situations are in equal measure hair-raising and exhilarating.

Pasted photograph by Fabio Bucciarelli for the New York Times and illustration by Jeremyville on Allen St, Manhattan, © Benjamin Petit. Courtesy of Dysturb

Pasted photograph by Fabio Bucciarelli for the New York Times and illustration by Jeremyville on Allen St, Manhattan, © Benjamin Petit. Courtesy of Dysturb

Featured in Life During Wartime: Art in the Age of Coronavirus, University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum lifeduringwartimeexhibition.org

Can you describe one of your most rewarding relationships with an artist – what factors made it enjoyable?

I don’t kiss and tell, so no names, but I love, LOVE, many of the artists I have professional relationships with. I believe in them and I am lucky enough to think that they believe in me. My working assumption is that they find me to be a good conversationalist and a decent interlocutor; someone they can bounce ideas off of who is responsible enough to trust with their projects. Amazingly, those artists and I have found that we have gotten to make shows and books together more than once, which is a truly rewarding thing. I’m pretty sure I learn much more from them than they do from me.

Jake and Dinos Chapman, The Disasters of Yoga II, 2019. Francisco de Goya Disasters of War. Selections from portfolio of eighty etchings reworked and improved with collage. Courtesy of Jake and Dinos Chapman, photographed by Ken Copsey. Featured in Life During Wartime: Art in the Age of Coronavirus, University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum lifeduringwartimeexhibition.org

What risks have you taken in curating that perhaps did not go so well but you learnt the most from?

I once tried to curate an art fair by picking artists from galleries and having the galleries foot the bill. It was the early 2000s, so the galleries let me, to mixed results. I’ve put that one on the good try shelf.

Gran Sur: Chilean Contemporary Art from the Engel Collection, Installation view, Alcalá 31, Madrid, Spain, 2020

What is one of your personal favourite exhibitions or events you have curated and why?

Unsurprisingly, the bigger projects I’ve done have been the most challenging. I curated a short lived but gargantuan biennial in Dublin (Dublin Contemporary 2011), and recently put together the largest ever exhibition of contemporary art from Chile (Gran Sur: Chilean Contemporary Art From the Engel Collection, at Alcalá 31 in Madrid through July 26). They both involved scores of artists and artworks and, generally speaking, a lot of moving parts. To that I can now add Life During Wartime: Art in the Age of Coronavirus, a 50+ artist virtual show hosted by the University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum, where I serve as Curator-at-Large (available at lifeduringwartimeexhibition.org through December 12). All of these shows have stretched my capacities as a thinker and an intellectual in the public sphere.

Narsiso Martinez, Good Farms, 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Charlie James Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo by Joshua Schaedel, Michael Underwood.

Featured in Life During Wartime: Art in the Age of Coronavirus, University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum lifeduringwartimeexhibition.org

What would you hope that people experience and learn from seeing one of your exhibitions or events?

I hope that they make direct connections from the art they encounter to the wider world. Whether we are talking about painting, sculpture, dance, installation, video, or any other medium, art should push people to think beyond the confines of the gallery or museum. My job, as I see it, is not unlike that of a fiction editor: to promote art as an exploration of human experience as revealed through formal values.

Do you help fundraise for the show you curate & if so how?

Rarely. But, for what it’s worth, a number of the recent shows I’ve organized and am organizing at USFCAM have received important grants funding.

What emerging artists are you excited by right now and why?

I will name names here, at the risk of forgetting folks, which I invariably will. There’s the London-based painter Francisco Rodriguez Pino, the Paris-based video artist Enrique Ramirez, the Cuban artivist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, the California painter and installation artist Narsiso Rodriguez, the Chilean multimedia artist Pilar Quinteros, the Miami-based video artist Edison Peñafiel, the Nicaraguan conceptualist Marcos Agudelo, the New York-based sculptor Kennedy Yanko, the Philadelphia-based painter and cartoonist Mark Thomas Gibson, the photographers Curran Hatleberg, Zora J. Murff and Anastasia Samoylova—who live and work, respectively, in Baltimore, Fayetteville, Arkansas, and Miami. I’ve had the good fortune to work with all of them and others during the last six months, and they’ve each reminded me of two things that should be head-slappingly obvious: one, there’s always something new under the sun; and, two, Ecclesiastes is overrated.

What helpful resources would you recommend to artists?

Look. Look a lot. Visit as many gallery and museum exhibitions as you can. Not only are they free resources (let’s leave U.S. museums out of the discussion for now), they are the best places to have visual encounters that will, artistically speaking, flip your lid. These spaces serve as literal libraries of the visual and should be understood as such. One of the few silver linings of the global COVID-19 quarantine is that many of these museums and galleries have established a parallel online presence. That means that, while this miserable lockdown continues, folks can explore these same libraries all over the world from the safety of their homes.

Do you have any advice for artists working with curators?

If possible, establish a partnership, and work with folks you trust and get on with. Life’s too damn short for networking.

Follow Christian on Instagram @cviverosfaune and visit his website https://www.cviverosfaune.com/